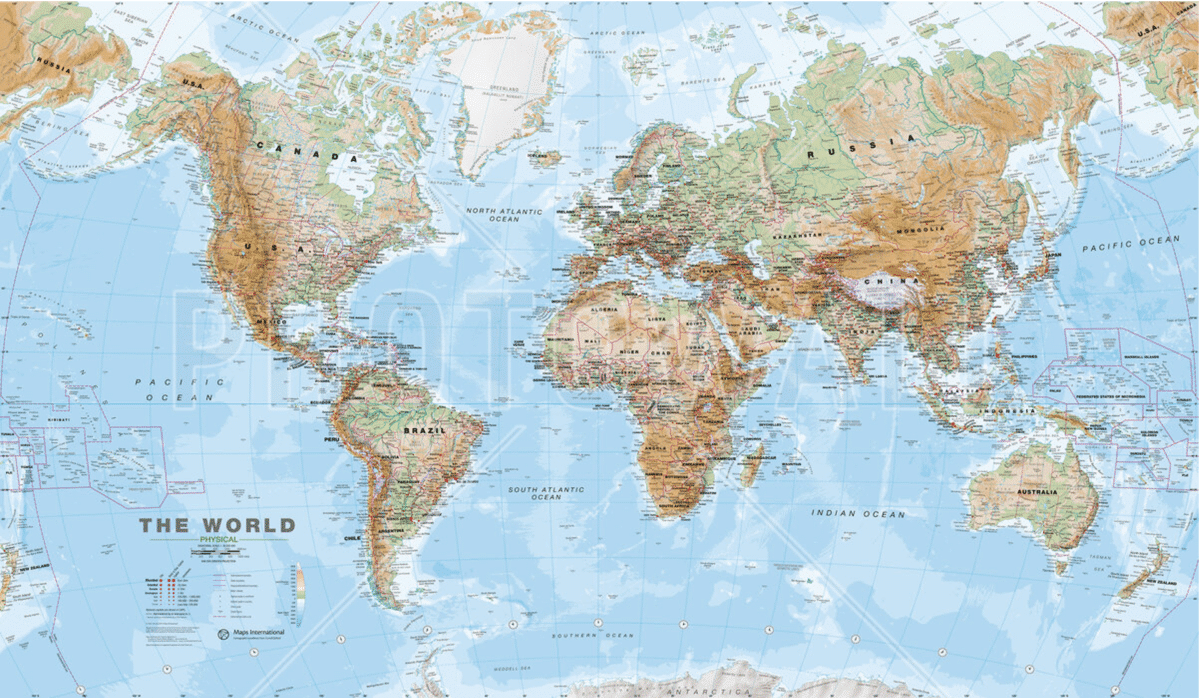

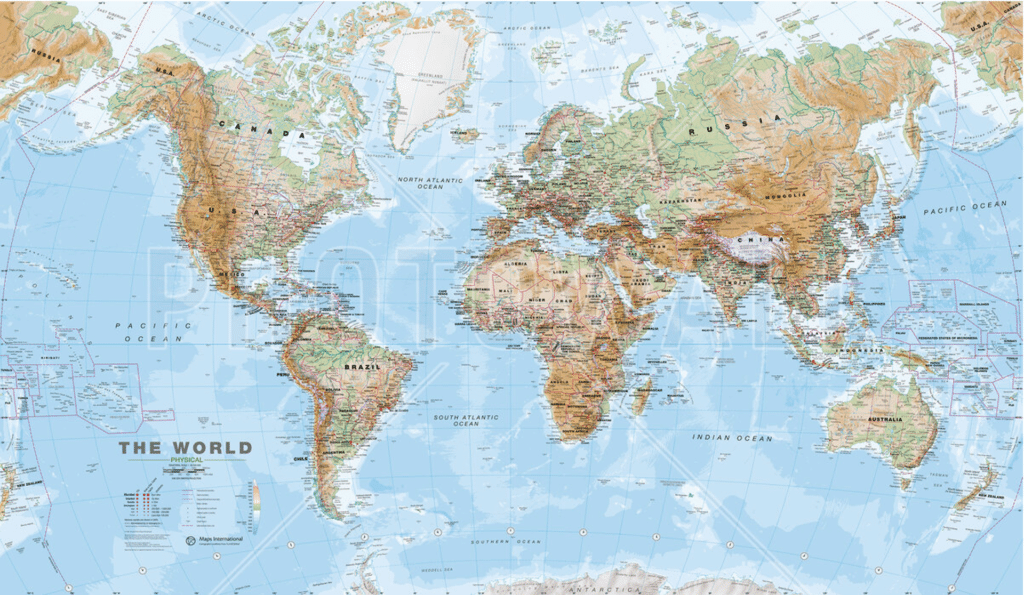

Whether traditionally strong or weak, here’s the areas I tend to favour at present.

One of the most important factors determining the value of a junior resource asset is its geographical location. The Fraser Institute is widely regarded as the best judge of the best places to invest, and therefore which jurisdictions are the most attractive for investment. Self-described as independent and impartial, the institute has nevertheless been involved in a number of scandals.

Why? The typical stuff — it’s based in Canada so as you’d expect, Canada is usually near the top of the pile. And it’s funded through donations, typically corporations instead of via government grants. The inevitable result is that it’s published a load of nonsense about tobacco and climate change, oil, and big pharma.

But the mining survey is usually pretty good. However, what it can fail to consider is the popularity of an area based on the value curve and risk-reward scale. In 2024, there are a few spots which I think are best to invest in.

Let’s dive in.

Mining jurisdictions to avoid

I’ll start with this: every country in South America is off the table. There is no point. Whether it’s taxes changing at a whim, projects being taken off licence holders, capital expenditure costs that mysteriously balloon for no reason, states deciding to randomly nationalise entire mineral deposits (Chile anyone?) it’s always the same.

When there’s an entire world out there, it simply is not worth the risk.

Then there’s Western Europe (excluding specific locations in Cornwall and Ireland). Getting any kind of mine going is a regulatory nightmare — just look at Savannah Resources. If Barroso was located in Nevada, the asset would be viewed as an excellent source of tax income; in Portugal where support for positive climate change policy is high (not surprising when your house is on the beach), locals are vehemently opposed to the development of critical minerals required to decarbonise the economy.

Zinnwald (Germany), Wolfsberg (Austria), Cinovec (Czech republic), Keliber (Finland)? Permitting is just a nightmare, and that’s before you start talking about Rio Tinto and Serbia.

Yes, the EC plans to enact its Critical Raw Materials Act to open critical minerals mines across Europe and reduce its dependency on China. I mean, it’s not going to finance it, but apparently that’s not a problem at all. Germany and France are considering €500 million+ in investments each, but so far this is just a plan.

It’s not hard to see why — funding Ukraine is expensive, the EU is still recovering from Brexit and the pandemic, and securing a long term future is less relevant than immediate pressing concerns. This is the attitude that gave China control of the world’s metals in the first place, but hey-ho.

For perspective, the EU consumes at least a quarter of the world’s metal production, but only about 3% of the global mineral exploration spend is based in Europe. And the supply and demand imbalances are well documented; the EC estimates the continent will need 60x more lithium in 2050 than it currently consumes.

But if a company wants to explore in Europe, then it’s almost always listed in Australia or Canada. For context, Toronto’s September TSX30 awards for ‘Excellence in Growth’ saw 7/30 companies in the mining sector with an average price increase of 615%.

But if not Europe, then where?

Top mining jurisdictions 2024

Broadly, you can categorise jurisdictions into ‘stronger’ and ‘weaker’ areas — with the stronger areas in North America and Australia, and the weaker areas in Africa.

I’m not sure these terms are particularly fair in 2024, but the general perception is that stronger areas take longer to permit mines, have more stable taxes and more regulation (which can slow down project development, but means you won’t have your licence stripped from you, or taxes increased midway through a decade-long mine build).

The downside is that building a mine is usually more capital expensive and then they have higher opex costs — which is why you are seeing nickel and lithium operations in Australia starting to reduce as metal prices fall. The sums don’t add up, but African operators can still keep going at present.

Weaker areas issue permits relatively quickly, and you can get started pretty fast. However, taxes tend to be less stable, and a different government can rapidly change the investing environment. For example, DROC owes Red Rock money apparently, and stripped AVZ of its Manono licence. Vast has been owed diamonds from Zimbabwe for a year. Atlantic Lithium had to suffer through a short selling report that alleged Ghanaian corruption when the Ewoyaa permit was issued, Zambia went crazy for a time…ad infinitum.

As a general rule, a find in a stronger jurisdiction is more valuable than in a weak one — but every investment case is unique. The other factor to consider (especially for UK investors) is the size of African countries; Kodal’s Bougouni deposit is in a relatively safe area of Mali, but if it was on the other side of the country, it would be far less attractive.

Other than the politics, there’s infrastructure to consider — find a Havieron next door to Telfer surrounded by road, rail, a port, power, water (perhaps too much) and that’s a different story to a similar gold deposit in the middle of the Botswana bush.

Finally, and this is crucial to consider; you need a skilled local labour force to get metal out of the ground. The alternative is getting a major on board with the financial firepower to train up a new team, which can be difficult.

The overarching question for a jurisdiction, or an asset in general, is whether it is good enough to attract external investment for your project: this could be a major buying shares in the company, agreeing an offtake pre-payment, a Joint Venture, an earn-in, or similar. But if you found some copper on the border of Ukraine and Russia the odds are that you’re going nowhere fast.

Stronger jurisdictions

Western Australia — has to be top of the list in terms of consistency and staying power. Masses of infrastructure. And it boasts extremely pro-mining politics, skilled labour, and there are tons of metal still out there to find. There’s also nobody living there at all, and because there is so much infrastructure and so many majors around, you only need to find a whiff of gold/copper or similar, and the majors will be happy to agree a deal which eventually ends with shareholders making money.

Nevada, US — Maybe best-known for Vegas (super fun, would recommend the Plaza on Main Street if young and on a budget), Nevada is easily the best US state to be making discoveries, though Arizona is also popular. The Nevada Mining Association is politically powerful, it has similar advantages to Western Australia in terms of infrastructure and personnel — and then there’s the Inflation Reduction Act alongside significant government grants to consider.

Saskatchewan, Canada — UK investors will know the Athabasca Basin is the premier location for uranium mineralisation, though this part of Canada is also a significant producer of both potash (world’s largest producer?) and helium. The helium/uranium dual mineralisation is similar to copper/gold — helium is created during the radioactive decay or uranium. Worth noting that when a company finds helium in the area, it’s often hard to know initially whether it’s a sign of a decent uranium deposit, or helium chamber (or if very lucky, both). It has its own mining association and companies are scrambling to stake land as uranium prices rise — the smarter operators have got the best bits already.

Ontario, Canada — a (relatively) smaller area focused around the Hemlo gold mine, which has dozens of operators exploring amid significant potential for investors. Relations with First Nations can be tricky to navigate at times, but there is only a small number of London-listed firms in the area. Would note that there are dozens of Canadian operators looking for minerals, but the area is a little slept on at present. However, Canada has harsh weather for about six months of the year, making exploration a difficult venture at times.

Greenland — a country which UK investors are largely ignoring to their detriment. Pro-mining population and politics, many brownfield sites to be reopened, and greenfield sites ready to be discovered. Significant mining history, with most deposits found in coastal areas where nothing lives. Perfectly located between Europe and the US, with little to no Chinese interference.

Weaker jurisdictions

Zambia — the place to be in 2024. The country committed economic suicide a few years ago and saw hundreds of millions of dollars of potential external investment desert the country. Since then, the President has reintroduced pro-mining politics with a particular focus on massively increasing copper exports and — shock, horror — the money has come back. Copper explorers are looking at some of the most prospective tenure on earth, so a diversified portfolio should yield solid results. Like most of this part of Africa, there is the rainy season to deal with. There’s also a pesky debt crisis on hand.

Zimbabwe — Fraser considers Zimbabwe as the least attractive mining jurisdiction in the world. I disagree, and they also put Zambia near the bottom of the pack. The country has attracted billions of dollars of Chinese investment — gold and lithium miners are only going to make money in the country. The most important factor is to ensure you are in with both the Chinese and the government. The key risk is the age of the President; while Zambia’s Hichilema is a comparatively spring chicken at 61, Zim’s Crocodile is a graceful 81.

Botswana — bordering Zimbabwe (and with a 150 metre border with Zambia), Botswana is one of Fraser’s best locations. To be fair, the country is arguably one of the safest in Africa, and politics has been stable since the BDP took power in 1962, and the party has continued to hold power through relatively free and fair elections since. One of the key issues is the reliance on diamond mining, a rock which may not keep its buying power as lab diamonds take off.

The bottom line

Investors need to take a broad view of what constitutes a quality mining jurisdiction, and factor this into investing decisions — and specifically whether a company’s market capitalisation reflects the advantages/setbacks of a particular state.

This is often more of an art than a science.

This article has been prepared for information purposes only by Charles Archer. It does not constitute advice, and no party accepts any liability for either accuracy or for investing decisions made using the information provided.

Further, it is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person in any country or jurisdiction where such distribution or use would be contrary to local law or regulation.