Your AIM minnow has reported ‘astounding’ assays. There’s no rule on hyperbole as long as the data is correct.

I’m going to start with the caveat.

Interpreting drilling results is far more complex than most retail investors think, and you could happily spend several days trying to figure out exactly what any one release actually implies. Covering everything would take hundreds of pages — and more technical details than most retail investors will understand.

However, what I’m trying to do with this piece is give the average trader a decent chance.

Let’s dive in.

When a company’s RNS says that their drilling campaign is ‘exceptional,’ ‘extraordinary,’ ‘remarkable’, or ‘outstanding,’ then all this tends to mean is that it’s worth doing some more drilling on the asset to establish a mineral resource/reserve. Companies spending millions of dollars on a drilling campaign only ever get two results:

- Not economically viable (a duster)

- Incredible! The best drill since Bosch was found in 1886.

The PR department is not going to let a junior say anything else because often the next step is dilution to fund the next stage of the campaign. This isn’t a negative — it’s the way exploration is funded if you haven’t managed to get a JV on board with big pockets. But it does mean that individual investors need to do some interpreting of results to get a realistic picture.

To improve your interpretation skills, here’s what to do: read the RNS at 7am. Stay off all social media, including bulletin boards, Twitter (stop trying to make X happen, it’s not going to happen), Telegram etc. Then try to guess how the market will react — while the herd does sometimes get it wrong, if you think a result is good and the share price falls, then your knowledge is lacking.

Once the drilling campaign is over, companies might talk about the quality of their resource, and again, you need to know what they mean. There are various classification systems of economic viability — the CRIRSCO International Reporting Template is usually the starting point, from which the Australian Joint Ore Reserves Committee (JORC Code 2012), the Canadian Institute of Mining, Metallurgy and Petroleum (CIM), and the Pan-European Reserves and Resources Reporting Committee (PERC) derive many of their standards.

This is not an exhaustible list, and each system uses different factors — in many cases, companies will use the system which best presents their economic case. However, as long as one of the major systems are used AND the exchange is regulated, you can be reasonably confident in the numbers.

To basics — a Mineral Resource is simply an occurrence or concentration of a material. They are categorised thusly:

- Inferred — low level of confidence, assumed but not verified. Based on limited work and can easily be downgraded or upgraded by further work.

- Indicated — reasonable level of confidence of deposit, including the economics. Further work less likely to move the needle too much either way.

- Measured — the gold standard (forgive the pun). A ‘competent’ person (varies by mining code, so be careful which one is used), has declared the estimate to be reasonably accurate to a high degree of confidence.

An outstanding inferred resource is far less valuable than a reasonable measured resource in most instances (because a bird in the hand is better than two in the bush, and also because you have invested significantly more already). As a caveat, even a measured resource can throw up curveballs when you actually start mining a deposit — you can only drill so many holes and at some point, you just have to go for it.

If you get to this stage, a major will usually put as offer on the table anyway — but quick-start options and the fact that many LEDCs often want to keep the junior involved (who brought the original investment into the country) is changing the industry.

Then there’s the Mineral Reserve, which is simply the economically viable portion of the Indicated/Measured Mineral Resource. These are usually subdivided into three categories:

- Possible — very low level of confidence. Circa 10% chance of success. This does not always mean the deposit is unviable, merely that not enough is known about it.

- Probable — lower level of confidence but sufficient to make a decision to mine. Circa 50% chance of success.

- Proved — far superior in every way, but much more expensive, and certain styles of mineralization means this is sometimes not possible. Circa 90% chance of success.

Converting a Mineral Resource into a Mineral Reserve considers factors including but not limited to:

- Mining factors

- Mineral processing factors

- Legal, marketing, and economic factors

- Infrastructure factors

- ESG factors

Again, there is some wiggle room between various schemes — but to illustrate, identical deposits, with one in the heart of Australia’s Pilbara region and another in the middle of Chad will have different Mineral Reserves, because you can economically extract more of the resource in Australia.

Or in other words: the Reserve is geological; the Resource is economical.

The other factor to consider is that Mineral Reserves change with commodity pricing — an opex-intensive greenfield lithium deposit in 2022 may not be viable in 2023, but several brownfield gold projects are about to fire up as the gold price exceeds record levels.

Indeed, one excellent investing strategy is to track brownfield sites and calculate the level of commodity pricing where it can be profitably reopened from care and maintenance — and buy shares when this is exceeded. These can relaunch must faster than other assets.

The study of studies

A key consideration of drill results is where the asset is in the feasibility timeline. One poor set of assays as part of a Definitive Feasibility Study is often simply part and parcel of outlining the extent of the deposit — a similarly poor result during the Scoping Study can kill the drill programme dead.

There are four key stages when it comes to determining economic feasibility, and in order they are:

- Scoping Study — the initial assessment to determine whether there is potential value, including preliminary economic analysis, basic engineering concerns and evaluation of the resource. This can include grab samples, remote sensing, desktop studies, magnetic geophysics, historic analysis etc. This is relatively cheap to conduct, with the idea being to build a data case for drilling investment. Occasionally there is some minor drilling.

- Pre-Feasibility Study (PFS) — far more detailed analysis to assess the economic viability and feasibility of an asset, including refining project parameters, looking at mining methods, checking infrastructure, and significant drilling.

- Definitive Feasibility Study (DFS) — comprehensive analysis of the asset, including economic, technical, drilling, environmental, and social considerations. A positive DFS is almost always followed by a decision to mine.

- Bankable Feasibility Study — far less well-known and not always necessary, but this step is more financial than geological, with the idea being to generate an extremely high level of certainty so that a company can shop around for lending. This study functions like the House Survey you are required to pay for before being allowed to take out a mortgage on a property.

Within all these studies, there are key terms to get to grips with if you want to understand what that key RNS is actually saying. However, it’s important to remember all studies are based on anticipated figures for an asset and may vary when production actually goes live. This is especially true for zoned pegmatites among other orebodies because ore quality will vary as you mine.

- Production — usually represented in tonnes per annum (tpa); the amount of ore that can be produced per year. You can then multiply this by the commodity pricing to get a general idea of revenue numbers. However, for minerals like lithium and titanium where the ore directly affects pricing (e.g., spodumene/petalite, or rutile/ilmenite), or simply multimineral deposits (commonly copper/gold), this can be complex.

- Capital Expenditure — commonly known by the portmanteau Capex, this represents upfront capital costs to construct the plant, including labour and raw materials. Beware this figure as in my experience it almost always ends up being higher than expected by the time the plant is built. If there’s little room for delay or error, factor this into your investment decision. In any JV or financing deal, look for an overrun budget. If there isn’t one, and the share price does not reflect this, run.

- Operating Costs — otherwise known as Opex, this is simply ongoing operational expenditure, such as labour, taxes, energy prices, and transportation. Some studies consider anything prior to production as capex, while others separate pre-production costs into capex and opex, and then calculate post-production opex separately.

- Net Present Value (NPV) — the US Dollar value of a project today if it is developed according to the feasibility study. For example, if the NPV is $300 million, then the project is worth $300 million in potential returns if developed. NPVs are almost always higher than company markets caps (though this narrows the longer the asset is mined, to a point), as there are always risks, alongside uncertainty that it will actually be developed.

One key misunderstanding concerning NPV is in asset ownership, including royalties. If a state (country’s government) considers 35% of an asset to be state-owned, that leaves 65% of the asset. If a junior then has a 30% economic interest in a JV with a major, it’s often only on 30% of the remaining 65%. Next imagine there’s a royalty or two over it — and then often share dilution at some point too. The NPV is for the asset, and you need to work out the value per share, which can be different to the IRR dependent on calculations.

- Internal Rate of Return (IRR) — potential return to investors willing to fund the project. This is causing some confusion nowadays as the IRR for new projects must be much higher than in the recent past, because the average retail investor can now get a 6% risk-free return in a bank account; so the IRR needs to be significantly higher than this to reflect the risk and attract investors. It’s worth keeping an eye on assets where the IRR is lower than this level because if rates start to fall, projects that are currently unviable will become investible.

- Project Payback Period — the amount of time before investors breakeven by getting back the capital invested. The shorter the payback the more attractive an asset is, though remember by the time an asset goes into production, commodity prices will have changed. Anyone trying to develop a gold asset on the assumption of $2000/oz for 15 years is being perhaps a tad unrealistic. Look for companies using realistic long-term commodity pricing.

What if an asset’s not feasible? The commodity is falling, investor sentiment is weak, the risk vs reward doesn’t cut the mustard…there’s plenty of reasons. You have a few choices:

- Undertake more exploration to increase the size/understanding of the deposit (hard to convince investors if it looks like a dud).

- Improve the technical aspects or metallurgy results to improve the economics (more common than you would think, can be a case of rushed work).

- Do nothing and wait for the market to turn.

- In a worst case scenario, do your best Michael Scott impression and declare bankruptcy! Not really, but investors need to accept that the point of drilling is to test for economic viability and not every asset works out.

On this last point, don’t blame the exploratory team when they find nothing. As an example, the first team to have a crack at the tenure where Havieron was found by Greatland Gold came back with dust. While some teams have more luck than others (read experience), the truth is that there is an element of chance.

Assumptions make an ass…

Remember, feasibility studies typically go out of date roughly two to three years after being formed, and they are only as good as their underlying assumptions. These can change in various ways (the most obvious, as mentioned above, being commodity pricing), but less obvious changes could be developing infrastructure. For example, a non-feasible lithium deposit in Zimbabwe today could become viable as infrastructure builds, locals upskill and the bull market returns.

If someone builds a processing plant next door to your deposit, then the value will rise substantially. On the flip side, if someone shuts down an undercapacity mine which you were planning on using in your PFS, that’s tough cookies.

The key assumptions to consider, however, include:

Commodity Pricing — again be super careful both about conservatism, and the orebody itself. Where there’s an offtake agreement, check whether pricing is fixed, variable, or has a floor/ceiling. As a general rule, the ceiling is worth the floor, though can take a chunk out of the asset’s value. Think of it like insurance; some policies are more expensive than others.

Cost Pricing — ever heard of inflation? There’s a reason why so many majors are getting married — Newmont and Newcrest, BHP and Oz, Allkem and Livent, Glencore and Teck, the Rinehart-Ellison shenanigans — the list is both endless and growing and it’s all about the ‘synergies.’ Inflation at 10% is a big problem if the asset’s commodity price isn’t moving with it, especially if followed by a recession.

Flow Sheet — this will be beyond most retail investors (and I usually call in for some help when undertaking analysis of this section). It’s the detailed design of how the plant will take some rock in the ground and turn it into saleable ore; sometimes this is as simple as crush, screen, sort — other times, it might as well be a diagram of a Tardis written in Gallifreyan. There are a thousand variables that vary from deposit to deposit, but the key thing you want to see is a start-to-finish chart.

Occasionally, you will have a base flow sheet, but with a modular design so that the plant can be upgraded dependent on the deposit or future cash flows. This should list the future upgrades by importance.

On a related note, the Front End Engineering Design (known as FEED, yet another snappy acronym) is the process where a consulting team usually made up of various engineers evaluate the project from a technical perspective to make improvements, similarly to how an editor goes over an author’s manuscript. This is often an ongoing, organic process that rises to meet challenges and changes as they occur.

Environmental Impact Assessment (EIS) — checks whether the project meets the country’s environmental guidelines and is massively more important than what most investors think, especially in MEDCs. Any problems or corporate ‘creativity’ and you can say sayonara to your mining licence overnight.

Production Schedule — how many tonnes the company plans to sell per year, which can be different to feasibility study production numbers. Feasibility studies usually consider the average, while the schedule will bely the reality that different projects deliver more/less in certain years dependent on the type of deposit and plans for future scaling.

Market Sensitivity Analysis — fondly known as the ‘ass report’ because it makes an ass of your assumptions (and often your asset!). This analysis shows how changes in assumptions change the project’s economics. Sales prices, opex, capex, mill feed grading et al can and do change when you actually get building, and there needs to be margin for error. If there’s not, then you either need a cheap entry point, or someone to stop you pressing the buy button.

Schedule — the proposed timeline from ‘first shovel’ to first production/constant production. This is usually displayed within a Gantt chart (activity against time axis’s), and the general idea is to hit each deadline on time, usually with each chunk of bank/major JV partner funding released upon each milestone. My advice? Always add 3-9 months to the schedule (budget for dilution and annoyed partners); schedules are always ridiculously optimistic to the point of lunacy, though the industry term is ‘aspirational.’

The bottom line is that the combined feasibility studies, including the assumptions, are both what you need to consider as an investor and also what the major/big bank is going to consider before splashing the cash. Assets usually cost hundreds of millions of dollars to develop, funding is hard to come by when rates are at 5%+, and that Final Investment Decision RNS is years away from the Scoping Study.

Drill, Baby Drill

Let’s say a company has done some initial scoping, and has got a JV, a loan, or gone to investors for an equity raising. It’s decided that there is sufficiently encouraging data to get drilling — but be careful because some companies would rather spend your cash than admit an asset isn’t worth it — and then there’s a long period of silence.

There’s nothing to say for several months because they’re getting on with drilling the deposit (fyi, often the best time to buy from a risk-reward perspective on the Lassonde Curve). Then the company comes back with results, and HOORAY! This gold deposit is so exceptional that we’re pretty confident that Bill Gates just buried thousands of ingots in the sand for his children a few decades ago, and just forgot about them.

Before you start buying your Lamborghini with the stock’s ticker on the numberplate, you might want to check what the results actually mean. If the share price rises sharply but the results are actually pretty average, it’s time to sell. And vice versa — if the stock falls even though the asset looks pretty good, then your knowledge edge will let you buy shares on the cheap. This is especially true of small cap growth stocks with tiny market caps that institutional investors are currently ignoring (to their detriment).

Interpreting Drill Results

The absolutely critical factor to understand before we get into geology is financial. If management and social media have set up expectations that the deposit will be a monster, a gamechanger, or similar then the share price will have this expectation priced in — and disappointment can see a crash even if the result is relatively good regardless. Conversely, low expectations and then a super discovery can see a share price rocket.

Now to the nitty gritty. Despite all the technical jargon, drilling is actually relatively simple. The drill rig goes into the ground and pulls out a sample (drill core) — which is logged by a geologist and then sent to a laboratory for testing (always check the lab’s credentials — a small number are seemingly staffed by illiterate Medieval peasants), and the log and lab result forms the drilling result (assay) for that hole in the campaign.

Tired of technical language and economic variables yet? They exist to make it harder for you to make an objective decision whether to invest or not — and generating consistent returns means getting to grips with the language.

But look — imagine the RNS comes out and says something along the lines of:

8.3m@0.43% Cu from 73m (AZSDFR007)

And you think: this is meaningless to me. No worries, I’m here to help:

- 8.3m — the length of mineralization intercepted

- @0.43% — the mineralization grade

- Cu —type of metal, by periodic table symbol, in this case copper

- From 73m — depth where the mineralization starts

- AZSDFR007 — the drill hole identifying number

I can’t explain the relevance of results to each mineral as this would take forever, but you can compare assays between companies to get a general idea of what’s good or not.

Now let’s break each of these terms down.

Length of Mineralisation Intercepted — the thicker or longer the mineralisation, the better the potential discovery is. However, thickness is typically only based on one direction of the drill hole, which doesn’t consider the angle of the drilling. A better measure is true thickness, where you also consider the angle.

For example, if the campaign intercepts 200m of mineralisation with a completely vertical hole, this is less significant than 100m of mineralisation at a 45 degree angle as this is better evidence of size — proving mineralisation extends both vertically and horizontally.

Mineralisation Grade — the concentration of the mineral in the intercept. The grade presented in the assay is the average grade, not the total grade, which can confuse newcomers to the space. Finding high-grade intercepts is important because low-grade ones are often excluded through the cut-off process.

Type of Metal — this is tricky because gold or iron grades are often comparable, while other minerals are not. As mentioned above, a titanium deposit composed of rutile can be worth as much as ten times an ilmenite deposit, while a spodumene lithium deposit is worth far more than a lepidolite deposit and so on and so forth. Often this level of detail is excluded or presented only qualitatively.

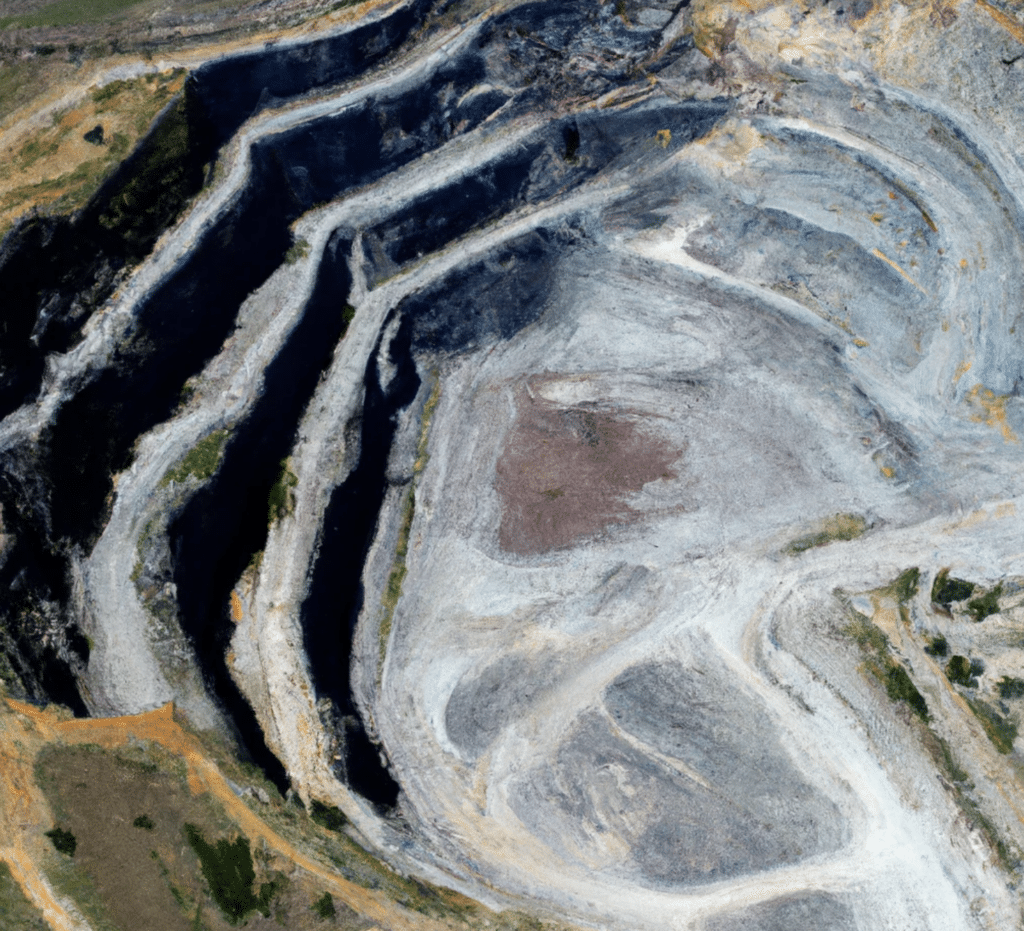

Depth Where Mineralization Starts — in the case above from 73m. That means you have to get through 73m of useless waste rock before getting to the ore, and this hugely impacts on asset economics. Shallow discoveries are amenable to low cost open pit mining, while deeper discoveries need to use expensive underground mining techniques. A reasonable grade close to the surface can be better than an excellent grade further down, especially in areas with less infrastructure.

Drill Hole Identifying Number — or ID, will also be found in a larger table within the RNS, usually after the CEO’s self-congratulatory paragraph on just why they deserve so many warrants. The holes will be mapped by the company so that you can check exactly where the hole was drilled on the asset, which is critical.

If the hole is in an area far from known mineralization, it suggests the deposit is larger than previously assumed and can be ‘extended.’ However, if it’s adjacent or between holes of known mineralization (the industry term is infill holes), there is no extensional upside, though it does still improve asset understanding.

When you start to understand how this all works, you will comprehend why expectations are so important. I lied to you before — it’s not just how the CEO has marketed expectations, or what the market expects — it’s about what YOU expect.

You should have a pretty firm range of expectations based on previous scoping or drill holes — and if an assay falls outside of this range, then it’s either time to pop the champagne or drive to Tesco for some Frosty Jack’s. Remember the task at the start when I said you should try to anticipate the market reaction to a drill hole? — it’s all about prior expectations, and you should be able to contextualize them using previous results.

Importantly, some assays will hit and others will miss — especially when a company is trying to extend an asset. The asset has to end somewhere, and the only way to know is to drill. As an aside, this is why ‘nearology’ is more of an art than a science; known assets are usually drilled until they can’t find anything else, and when you go drilling close to a proven asset, you’re often hoping to find something missed, or else an extension of the same mineralization which may or may not be there.

As an example, the African Copperbelt between Northern Zambia and Southern DROC has seen drilling campaigns return both truly exceptional deposits and absolute dusters.

Critically, you should look both at holes that strike mineralization and also those which hit nothing. This is key to expectations; CEOs will highlight the best hole(s), but the entire picture is needed to understand potential value. In particular, you need to be able to see a map of the holes drilled to gain a wider understanding of where the best results are being found. Five great holes all five metres from each other won’t even buy you breakfast in Wetherspoon.

Pitfalls to watch out for

So far, I’ve covered how to interpret what’s reported in your RNS. Now I’ll cover how to interpret what is not reported, which is arguably more important. In other words, the red flags.

Note that these aren’t always a problem, but to gain an edge in the market you need to be able to understand both what a company’s CEO wants you to understand and also what they’d prefer you ignore before making the decision to buy.

In order of my pet peeves:

1. Drilling holes too close to an exceptional intersection — yes infill drilling is important. What’s not useful is when the company drills too many holes in one area in order to generate a series of RNSs which imply an asset is far higher quality than can be proven. It’s like weighing the same pig in the passel every week — it doesn’t make the average hog in the herd any fatter.

A lot of this is timing though; closer drill holes after you have mapped out a general zone is fine, biased drilling before you have established the edges of the asset is not.

2. Highlighting the highlights — yes, of course you can put the best drill result at the top of the RNS. But you also have to include the complete set of results underneath alongside mapping so that serious investors can decide for themselves whether the campaign merits an investment vis-à-vis the share price. Two holes and no other data? Run, unless those are the only two holes drilled to date.

3. Gaps in hole numbers — related but no less infuriating is where there are gaps in the drill hole numbers. This is usually easy to discern, and often there are reasons — but they should be disclosed. Drilling problems, technical issues, a lost sample (you’re in the depths of Canadian winter, it happens), a few results left outstanding…it’s okay to have a few gaps.

But often the plan is to omit the worst holes on the pretext of issues, let the share price rise, place some shares, and then quietly release the remaining drill results. Is this ethical? No. Does it happen? Yes. Can you avoid it? If you can count.

4. Using a computer model to make a deposit seem larger/simpler than it is — yes it might look very fancy, but a pretty picture can mask difficulties in the asset. Generating a shell might make it look like a well defined resource, but deeper dives usually show a computer shell is based on weak assumptions.

5. Presenting length of mineralised interception as true width — results can seem astounding, but when you factor in angles a high grade can rapidly be tempered by true width. An intercept might be reported as 200m long and then further down in the RNS, the true width is actually 15m. Extreme I know, but it happens. If you’re confused about true width, YouTube it; this is one area where video is easier to understand than words.

6. Ignoring the importance of water and/or contaminants — for example, a lithium deposit high in mica or iron can be unviable even if the lithium grade is high. The same is true of a gold deposit with significant aquifer issues. Where a drilling RNS attempts to brush over obvious viability problems, run. Run fast.

7. Using optimal holes to create the illusion of an exceptional cross-section — a sneaky practice whereby the company uses holes one through nine to present the impression of an exceptional mineralised zone but forgets the inconvenient hole number AZRDGN000010 right in the middle of the cross section which yielded zero or lower mineralisation. This is usually spotted fairly quickly but can be missed when the missing hole is off-centre.

8. Smearing — no laughing in the back. This is serious business, but I don’t find this one too annoying because I view it as fraud and simply ignore any company which has ever engaged in the practice. Best practice is to apply a top-cut to grade, but some companies choose to average out higher grades from narrow intercepts to make it seem like an asset is higher quality and more consistent than in reality. It’s sometimes a genuine mistake, but my view is that this particular error is rarely unintentional, and frustratingly it’s very difficult to spot.

9. Presenting economic numbers in a manner designed to trick investors — say a company is calculating an NPV for a gold-copper deposit. It uses a very conservative gold price of $1,000/oz and this increases the relative importance of the copper as it’s usually expressed in AuEq (gold equivalent). The investor then applies the current spot gold price to the resource and takes away the best case scenarios for both the gold and the copper, rather than a realistic interpretation of both.

10. In the same vein, when companies ignore treatment charges and/or royalties when calculating asset attractiveness and marketing it to potential investors. The NPV can be completely correct, but the actual profitable return is based on multiple complex factors, so it can be tempting to ignore one or two. Please stop doing this, it’s annoying and yes it might be hidden somewhere at the bottom of page 17 but it would make life so much easier to just be up front.

The bottom line

Interpreting resources, studies, drilling, and asset assumptions is a skill that takes years to develop. You can still get it wrong, but the key thing to understand is that it’s not the title of the RNS that matters, it’s the lines of content — and the reading between them.

One final thought: while it may seem that initial drilling success is often a case of luck, usually the same teams of managers and engineers consistently make solid finds. Drilling is more poker than roulette — luck is an element but is dominated by skill. Research the names before you commit.

Good luck.

This article has been prepared for information purposes only by Charles Archer. It does not constitute advice, and no party accepts any liability for either accuracy or for investing decisions made using the information provided.

Further, it is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person in any country or jurisdiction where such distribution or use would be contrary to local law or regulation.