A snapshot macroanalysis of uranium in 2023. Next week, coverage of the best uranium small caps for high-risk investors.

Those of you who have followed me for some time, both here at Investing Strategy and elsewhere, will know that I follow the battery metals space closely with a huge focus on lithium and graphite.

Top lithium picks — PREM, KOD, MARU, ALL.

Top graphite stocks — TGR, BRES, GROC, MARU

Top REEs — MKA However, I tend to invest in large-cap copper stocks like Antofagasta, Freeport-McMoRan, and Southern Copper — not because there are no decent smaller copper plays, but because the titans are currently severely undervalued given the copper supply gap, and the increased risk of small pure-play copper investing simply isn’t worth it from my own personal risk-reward perspective.

Investing Strategy

I aim to time investments close to the bottom of the market at the moment of maximum fear; reasoning that whatever short-term problems there occasionally are, the mineral deposits remain in the ground and there’s a huge financial incentive to dig them up.

And then I hold these stocks, usually for years, ignoring the noise and volatility that is symptomatic of the FTSE AIM market. My guiding principle for years has been that there is not enough lithium, graphite, or REEs available to western markets for anticipated future demand — the west now seems to be waking up to this, and China is responding with aggressive and very favourable terms for small cap explorers and producers.

I also invest heavily in biotechs — but unlike small cap miners where I expect most to be rewarding, I fully expect several of my biotech investments to fail and others to wildly succeed.

I was buying up the lithium explorers in mid-2019 at rock-bottom prices, started buying graphite shares in mid-2022, and have recently been adding larger copper stocks to my SIPP for very long-term exposure.

I think that ex-China and ex-Turkey sources of graphite will become extremely desirable as Sino-US and EU-Turkish relations continue to deteriorate, perhaps later this year or in early 2024. Copper companies could be depressed by the anticipated global downturn, though I expect they will surge in mid-2024.

But I’m always thinking at least two years ahead. And if there’s a mineral that’s going to outperform in 2025, then it’s going to be uranium.

A short history of nuclear

Uranium has been unpopular for decades for various reasons. To start with, its radioactive nature means that it’s impossible to buy the material and take direct physical possession.

But the bigger issue is a historical distrust of nuclear power — and not without good reason. In Japan, the horrors of Hiroshima, Nagasaki and Fukushima are burnt into the public consciousness — the country’s nuclear power usage has fallen from 30% since Fukushima to 7% today, but it now expects to ramp this back up to 20%.

In Ukraine, the 1,000 square mile Chernobyl nuclear exclusion zone serves as testament to what happens when things go wrong. The disaster cost $68 billion to contain, cost many thousands of lives, and could well be repeated at Zaporizhzhia as the Russia-Ukraine war rages on.

While nuclear is termed by some as ‘clean’ energy, current nuclear power relies on nuclear fission — which produces extremely dangerous waste, which is usually then stored in an underground repository within cannisters and sealed with rocks and clay.

There’s an entire fascinating field — termed nuclear semiotics — which concerns designing messages to warn future generations about this danger. Indeed, Australia has banned nuclear power despite having the largest uranium deposits in the world.

But the world is facing hard choices, and nuclear is looking more attractive. Indeed, the UK just reclassified nuclear as green, despite the waste produced, to incentivise further development.

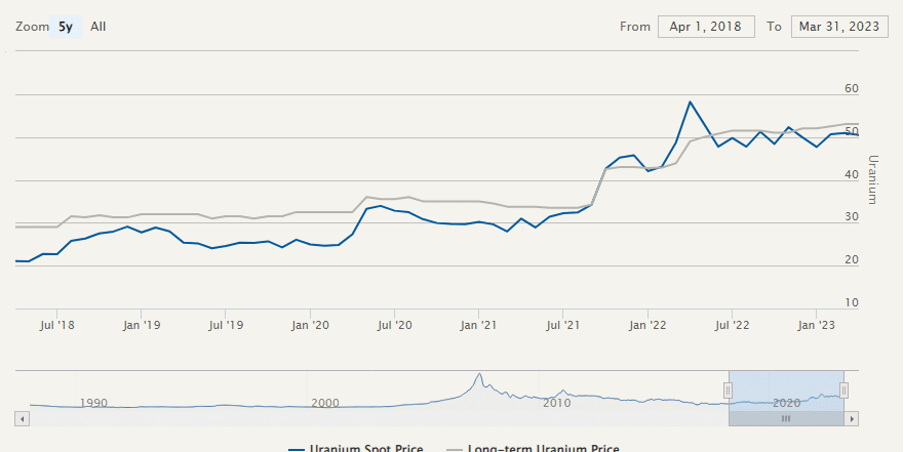

It’s worth noting that the uranium price is continuing to trend higher — and accordingly, a race for resources could be coming soon.

Uranium stocks in 2025: 4 factors to consider

1. Energy security

Whether you believe that fossil fuels will run out, it’s undeniable that most of our oil and gas comes from unsavoury regimes abroad. Of course, this is partly political insanity given windfall taxes and regulations keeping our own North Sea fossil fuels in the ground, but that’s government for you.

It’s the same with our carbon emissions — it’s all very well lecturing others, but we have all our plastic tat manufactured and shipped over from China.

But what happens when you rely on these regimes for energy security? Germany is the classic test case. After Chernobyl, Germany shut down virtually all of its nuclear reactors, choosing to rely on Russian oil and gas. Cue the Ukraine War in March 2022 — the country was up the creek without a paddle — and Putin knew it.

With Russian sources no longer politically palatable, energy prices have shot up across Europe, and we’re all paying for and going to continue to pay for it. Yes, there have been advances in wind and solar, but nuclear is different in that it provides consistent supply — already at 10% of global energy needs.

According to the US International Energy Agency, global energy demand has already trebled between 1980 and 2018. And electricity demand is rising faster than renewables can keep up.

2. BRICS supremacy

I don’t consider that the BRICS countries will be able to trust each other enough to create a new global currency, in the same way that I don’t think OPEC members trust each other to stick to recently announced production cuts.

However, it’s clear that the global sands of power are shifting. The west will soon get into gear, but China — as per usual — is ahead of the curve. The country currently accounts for over a third of global greenhouse emissions, but has set aside $440 billion for clean energy by 2060 — and plans to build 150 new reactors in the next 15 years.

At present, there are just 440 online worldwide. As global international relations continue to deteriorate, oil suppliers may be forced to choose sides. Consider the reaction to a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, and where the west may want to be in terms of alternative power supplies.

In 2023, the idea that Saudi Arabia could cut us off is laughable. Two years from now, the world order may look different.

3. Kazakhstan instability

Kazakhstan is not just the fictional home of Borat — state-owned Kazatomprom is also the supplier of 43% of the world’s uranium as of 2019. The country upped production after Fukushima, forcing other suppliers out of business, who were seeing a huge fall in uranium demand and were also unable to cut supply to support prices.

There was serious unrest in 2022 that came close to a government coup — and this was only stemmed when Russian military was sent in to bring back order. This won’t be possible next time, as Russia is now otherwise engaged. And regardless, relying on one soviet satellite to power much of the world’s nuclear reactors is perhaps not the best idea.

France has spent much of the past year or so mocking Germany for its reliance on Russian oil and gas, safe in the knowledge that 70% of its own power comes from Nuclear. But nuclear is powered by uranium — and France gets much of its supply from a country that is essentially Russia’s little brother.

Alternative sources will be needed soon. BHP’s exploration division is actively seeking new uranium acquisitions, and the rest won’t be far behind.

4. Technological advancement

Two tech advances are making nuclear power more palatable for the wider general public — in the UK, 20% of all electricity is already nuclear-powered.

Setting aside wider climate change concerns, the first is the development of small modular reactors — popularised in the UK by Rolls-Royce designs, but many other companies are already coming out with their own ideas.

These are smaller plants, roughly the size of two football pitches, and would cause a local, not a national disaster, in case something went wrong. They are also much cheaper than the traditional alternatives.

Opposition is relatively muted compared to larger projects such as Hinkley Point C.

The second is the incredible developments in the nuclear fusion space. US researchers at the National Ignition Facility at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) in California overcame the key nuclear fusion barrier last December, producing more energy from a fusion experiment than was put in.

LLNL Director Dr Kim Budil speculates that even with significant hurdles ahead, ‘with concerted efforts and investment, a few decades of research on the underlying technologies could put us in a position to build a power plant.’

Fusion power produces zero emissions and only a tiny amount of waste — and is therefore the holy grail of limitless energy. Budil is probably underselling the pace of technological advancement, and further breakthroughs could render oil redundant completely.

If this sounds fanciful — well, you’re reading this article on a screen powered by a rock that we tricked into thinking.

High-risk small cap uranium miners will be covered next week. Stay tuned.

This article has been prepared for information purposes only by Charles Archer. It does not constitute advice, and no party accepts any liability for either accuracy or for investing decisions made using the information provided.

Further, it is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person in any country or jurisdiction where such distribution or use would be contrary to local law or regulation.