With StockBox on-site at PREM’s Zulu Lithium Project, excited investors should consider the limits of RNS regulations and guidance.

With Mark EJ Fairbairn of StockBox currently on-site at Premier African Minerals’ Zulu Lithium Project, one question that seems to be popping up on a regular basis is the extent to which Mark can deliver information which has not been sent out via the Regulatory News Service (RNS).

Mark is well aware that there are limits to what he can say, record, or opinionize. These rules don’t just apply to PREM, but also to the hundreds of other companies which rely on the RNS.

And there are many companies which toe a fine line whereby they release information via social media and then RNS it. Companies like ANGS, GCAT, KOD, MARU among others use social media to disclose snippets of information either before an official RNS, or as an alternative.

This begs the question: what must be RNS’d, and what doesn’t have to be?

Regulatory News Service explained

When a company decides to launch an IPO in London, whether dual listing from elsewhere or moving out of private ownership, it must start to engage in legally mandated transparency for shareholders. A large part of this is reporting important new information to shareholders which could have a material impact on the share price within a reasonably rapid timeframe.

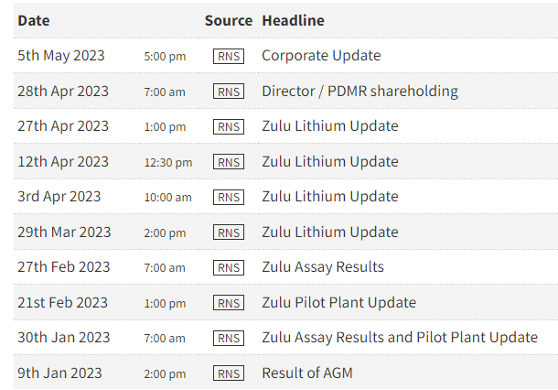

Most companies communicate with shareholders and the market in general via the Regulatory News Service (RNS), which is owned by the London Stock Exchange (LSEG). Almost 350,000 RNSs are issued every year and LSEG estimates that circa 75% of all price-sensitive UK company announcements are made through the service.

It’s worth noting that companies don’t HAVE to distribute all regulatory news through a RNS — they can also use services such as GlobeNewswire and BusinessWire. Many simultaneously release pertinent news on their own website, but investors also tend to use sites such as London South East to look for RNSs across a range of companies rather than checking individual sites. Of course, there is occasionally a very small lag, so investors should be careful doing this.

Most announcements are made at 7am or at 5pm, meaning that the market will have at least an hour, and sometimes overnight or even an entire weekend to digest any important news. It’s considered bad form to release an RNS during the day as it creates unnecessary extra volatility.

I often joke that this is because some investors can’t read, but the truth is that many double-edged announcements declaring both positive and negative news can make judging whether to buy, stick, or sell fairly difficult. On top of this, many traders use AI to auto-trade shares, or operate a risky ‘buy the rumour, sell the news’ strategy.

The common exceptions to mid-day RNSs are when a major shareholder changes their holding, which should be reported as soon as possible, or when the chance of insider information leaking is high — a good example was when HARL announced it had won preferred bidder status for the FSS contract at 10.58am on 16 November 2022.

What has to be disclosed?

When, how, and why a company must update the wider market is governed by an extremely complex spiderweb of regulations set down by the FCA, LSEG, and the EU (rules created by the latter are considered more as good practice since Brexit — but most companies follow them anyway).

These regulations have been further interpreted through hundreds of instances of case law to develop a fair middle ground. For context, when you pay masses of CGT and dividend tax, some of this money is being used to regulate the market.

The most important point is that a company MUST notify the market through an approved regulatory information service (usually the RNS) any INSIDE INFORMATION pertinent to that company. A company will usually check with their stockbroker what might be considered to be insider information or not.

Inside information is harder to classify than it might appear. It must:

- not be generally available

- be of a precise nature and specific to the company

- be price sensitive to the company’s share price if it were to be made generally available

Like much else in law, a company must consider what ‘the man on the Clapham Omnibus’ otherwise referred to as an objective outsider — would consider to be insider information.

For example, could a trader looking to make money from PREM’s day-to-day share price movements use non-RNS’d information to generate a profit? Hard examples, where there is no gray area, include where there has been a material change to a company’s finances, financial results, a big contract win or loss, or change in the value of an asset.

If news is unexpected, then companies are allowed to delay for a reasonable period to establish all facts — for example, if a mining operation has been hit by an earthquake or the CEO has died (sadly, I’ve experienced both of these). If information starts to be leaked, then a company has to release a ‘holding statement’ containing as much accurate information as possible, before fleshing the statement out with details later on.

A company can also hold off on news that would ‘prejudice its legitimate interests’ — but needs to ensure that this news remains confidential to insiders until RNS’d. A good example — and all too common on AIM — is where a company needs to raise some cash or is in financial difficulty.

This means it can conduct conversations with current and potential lenders without having to tell the market. If it then can’t get favourable terms, there’s then often accusations of rug-pulling and anger that investors haven’t been kept in the loop when the news eventually comes out.

However, the powers that be judge that it’s better for investors overall that management can conduct financially detailed conversations without issuing an RNS immediately as it protects the share price from falls, especially where finance is eventually agreed on favourable terms. This is a contentious stance, and one where there is some grey area.

These rules are all in place to ensure a ‘level playing field’ to prevent insider trading and create a culture of openness.

What doesn’t have to be officially RNS’d?

Where a company’s share price is being hit or encouraged by an unsubstantiated rumour, it doesn’t have to send out an RNS. However, if the rumour starts to get out of hand, there’s usually strong encouragement to set the record straight. A good example was when Silicon Valley Bank collapsed — most tech companies rushed to clarify, especially where there was no exposure.

Some companies will give analysts some ‘private guidance’ to help make earnings forecasts — the justification is that just because some information is unpublished does not make it insider information. This is another contentious area — the test is often whether the information given could be garnered by an outsider — though in practice an outsider would need to dedicate days of research to get the same information on their own.

Unofficially, a 10% share price rise or fall is enough to constitute a ‘significant’ movement, but the FCA has been clear that this 10% rule isn’t an official regulation or guidance. This is to prevent unscrupulous traders from profiting by bending the rules to trade on insider information that might only see a 7-8% share price swing.

But in reality, the 10% rule does exist as a decent rule of thumb. This is because of the ‘floodgates’ argument — if the FCA took every firm to task for every minor slip or mistake, it would open the floodgates to court cases and overwhelm the court system. There is some leeway for human mistakes with minor errors — every CEO giving an interview has at one point mistakenly said too much.

In essence, the FCA is always seeking a balance between shareholder rights and corporate practicality (it’s not reasonable to expect the smallest FTSE companies to RNS every little thing). More leeway is often given to FTSE AIM companies who lack the resources to dot every ‘i’ and cross every ‘t’ in real time.

The grey area

I’ve already highlighted a couple of grey areas above, but it can be very difficult to distinguish between inside information that must be RNS’s and information which doesn’t have to be.

In the course of my work, I often sign non-disclosure agreements covering lots of the analysis I do — such that what makes it to Twitter is less than 50% of my workload.

Usually, information is categorised on a scale of Confidential 1 (C1) to Confidential 4 (C4). There’s never a problem with discussing Level 1 information — but if I were to reveal Level 4 information, I would expose myself to a lawsuit. Companies often use this scale, or similar, to determine what is and is not insider information.

Likewise, I always use disclaimers — ‘this is not financial advice’ etc — alongside carefully selected journalistic language to ensure that readers aren’t relying on definitive statements.

Companies can be fined millions for inferior disclosures, or for failing to disclose material information at all. However, this doesn’t mean that everything relevant will be in an RNS, or that extra information can’t be released outside of the RNS.

For example, specific wording can provide extra clues. If an RNS says trading is ‘broadly’ in line with expectations, then it implies that trading is actually slightly worse than expected. If it says management are ‘strongly encouraged’ by a development, this might excite investors but has no legal weight as there is no definitive statement.

Likewise, a director shareholding, or major shareholding, going up or down rarely comes with a reason. However, when an activist investor is building a position, it’s often because they are going to consider a takeover bid. Management may know this, but don’t have to tell investors.

And where a manager is selling shares, this is often interpreted as a bad sign — though often a quick LinkedIn or Twitter visit to their profile might show otherwise. For example, the CEO of one of my holdings recently sold a large number of shares to pay for private cancer care for their mother. Often, it’s more prosaic matters like paying for a divorce or a personal tax bill.

There’s also factors like company secrets or patented tech. Companies don’t have to disclose patented tech advances for obvious reasons — which can create a divergence between a share price and the company’s true value.

PREM: what to watch for

With Mark walking around the Zulu Project site and launching a live broadcast at 4pm on Monday, investors should look for the grey areas to get more information.

For many companies, there’s an informal litmus test many analysts call the ‘lunchbox test.’ Essentially, if a PREM worker’s wife came on site to bring her husband a packed lunch, anything she can see on the way in and out of the site can’t be considered inside information. This is because an outsider could easily garner this information with little effort.

Given Mark’s visit, I expect there will be an RNS this week detailing developments at Zulu, but investors looking ahead should be hunting for grey area clues. Piles of spodumene on-site which any worker can see is a good example, though there are many others.

When assessing the three-day visit, consider what must be officially released and what can be revealed before an RNS. And look for the middle word-fudging ground — beyond the excellent general coverage, that’s where the value is.

This article has been prepared for information purposes only by Charles Archer. It does not constitute advice, and no party accepts any liability for either accuracy or for investing decisions made using the information provided.

Further, it is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person in any country or jurisdiction where such distribution or use would be contrary to local law or regulation.