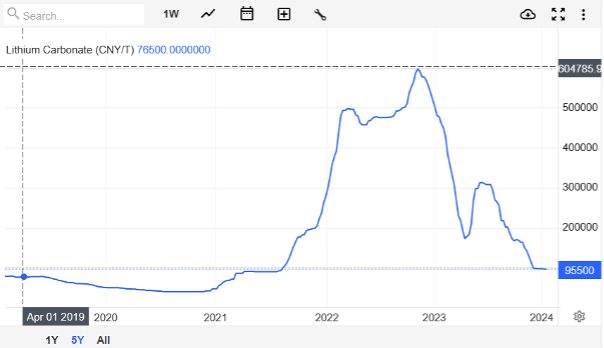

Lithium collapsed in 2023 and continues to fall to unsustainable levels. What’s happened, and crucially, what happens next?

Before I get started, it’s worth noting that this entire piece is subjective opinion. Others will disagree and it’s important to read alternative voices when making any investment decision. The other factor to consider is that this is a brief overview of several key points and not a comprehensive report.

Having said that, I think it’s important to take a macroeconomic look at what’s going on with lithium — and whether there may be brighter horizons in the near term.

Let’s dive in.

What’s happened?

During the pandemic, and let’s face it years before that, billions of dollars, pounds, euros et al were printed to stimulate the markets after the 2008 Global Financial Crisis — compounded with more than a decade of sub-1% interest rates — and huge Chinese state subsidies on manufacturing.

The natural consequence was that capex-heavy activity in the EV space became very affordable and electric vehicles went from a quirk in 2019 to a growing mainstay of the auto economy a couple of years later. For context, circa 60% of lithium mined is destined for EV batteries.

And just look at Tesla:

Of course, some perspective is important: 2022 saw EV sales exceed 10 million — globally 14% of all new cars were electric, up from 9% in 2021 and 5% in 2020. 2023 will likely see similar growth. But the vast, vast majority of cars on the road currently are still traditional ICE vehicles — and rapid EV growth has to an extent been a symptom of ultraloose monetary policy and specific subsidies.

But at points during 2022, Tesla’s market capitalisation superseded every other auto manufacturer combined. Then came the pandemic hangover and Ukraine War — where multiple countries briefly hit double-digit inflation, forcing monetary policy to respond via quantitative tightening and rate rises.

Rates rose sharply, the money taps were turned off, and the rEVolution came into question. But even into late 2022, SP Global was still bullish on the silvery-alkali metal. However, when a bubble rises, it must also pop. 2023 saw prices collapse by almost 80%, now to levels last seen in mid-2021.

Other than monetary policy, what happened?

Actually, that’s the biggest problem.

Let’s consider the legal environment: the UK has pushed back regulation to force auto makers to make only EVs from 2030 to 2035. Similar legislation is in place across the developed world, but the reality is that whether in the US where the Federal target is for 50% of news cars to be EVs from 2030, or in Australia where there is a much woollier fuel efficiency target — you cannot decarbonise the globe on expensive money.

Infrastructure costs alone are incredible — consider the US Inflation Reduction Act — Goldman Sachs puts the true cost of subsidies alone at $1.2 trillion, and with rates where they are US national debt is ballooning to unsustainable levels.

General Motors, LG Energy, Honda, Ford, and others have all dramatically scaled back EV plans, essentially because rising rates have both increased the cost of manufacture, and also reduced consumer appetite. This has created a global supply glut for the metal — and Benchmark Mineral Intelligence considers that the deficit will not return to 2028.

Away from EVs, Orsted — the world’s largest wind farm developer — has abandoned US offshore wind projects — Ocean Wind 1 and 2 — tanking a $4 billion hit because the economics simply no longer added up.

The other problem child is, of course, China. In January 2023, the Communist country scrapped a huge EV subsidy that had been in place for a decade. Of course, the major players in the industry knew beforehand, so stocked up on lithium while the subsidy was in place — ironically paying more than if they had simply waited for the price reduction over 2023.

However, China and by extension Chinese companies, value supply over price. You now have a situation where these stockpiles are being used up instead of Chinese companies ordering lithium from suppliers. And because demand for EVs in China is temporarily lower due to the removal of subsidies, slowing growth, and the higher cost of money, suppliers are neither having so sell at very low prices or stop production.

Indeed, CATL knew what was coming —offering discounts on batteries to Chinese EV manufacturers a month later, giving them a huge cost edge over competitors. This came with an in-built assumption that lithium carbonate prices would more than halve over 2023.

Remember, there is no private finance in China — the entire country is controlled by the Communist party. While the state had no control over western interest rates, it carefully removed subsidies to make lithium production unviable — driving share prices and offtake possibilities lower.

Once Chinese companies have secured offtake agreements — see Ganfeng and Pilbara — or JVs/buyouts with every operator from Africa to South America on its terms, it will reintroduce the subsidies as rates come down, having bought assets/production rights at the rock bottom.

The western boom and bust mining supercycle is not set up to deal with this.

However, while BMI is a very good source of information, I am not sure they have considered what happens when the price you can fetch for spodumene on the market is less than the cost of manufacture.

For context, SC6 is fetching circa $1,000 per ton, with low-iron higher grades perhaps as much as $1,600. Higher cost operators such as Core Lithium are already putting plants into care and maintenance — while larger operators including Albemarle and SQM are stockpiling the metal and reducing expansionary efforts.

What does this mean? Well you might argue that when lithium prices recover, these opex-heavy operators will jump back online, while the majors will sell their stockpiles, keeping a lid on the lithium price. And you’d be right. However, as we know, in 2022 there was nowhere near enough lithium supply for demand — and if that demand comes back as rates start to subside, you will be right back to the status quo.

With one difference.

It can take a decade to go from lithium discovery to operating mine. And all the new mines that were due to come online on the back of Definitive Feasibility Studies that had lithium at a huge premium to today’s price are now being paused for development.

This will leave China still in control of the lithium market when the bull market returns. If there weren’t enough projects before, what happens when development is paused on the new projects that analysts assume will be online and will instead simply be cancelled?

The other factor to consider from 2023 is the advancement of alternative battery solutions, or hydrogen. I believe hydrogen will be a contender in future years — though infrastructure requirements mean it will take years from now to be an issue. I don’t think sodium can contend with lithium for basic chemical reasons — lithium is the lightest and most conductive metal.

Where next for lithium pricing?

If you want to predict the long-term lithium scenario, then consider this:

Goldman Sachs has been reasonable accurate in its forecasts. For 2024, it expects to see SC6 average $1,250/tonne ($250 a tonne more than present). However, it’s expecting a small decline at the start of 2025 before rising thereafter.

Rio Tinto has forecast a 945% uplift in lithium demand over the next ten years — and we know that supply, which is already based on forecasts from when prices were higher AND with a much higher project success rate than is realistic — is starting to fall.

AustralianSuper — the largest pension fund in Australia worth US$200 billion — plans to double its holdings in ASX lithium stocks over the next five years. Manager Luke Smith notes that ‘the biggest opportunities for us as investors at AustralianSuper is when the prices are at cycle bottoms…we’re seeing now the opportunity become more attractive.’

The fund increased its stake in PLS to 6.12% a couple of weeks ago, and currently holds AU$1 billion of ASX lithium stocks. It expects supply issues to re-emerge over the longer term, taking a view of ‘what will happen over the remainder of the 2020s’ rather than a short term mindset.

Then there’s IFM Investors — another ASX superduperfund, owned by 17 Australian superfunds. It’s planning to invest £10 billion into UK renewable energy infrastructure by 2027.

The bottom line is that investment banks like Goldman work on 12-month timeframes. The majors like Rio work on ten year timelines, and pension funds — like the Chinese — work on multi-decade timelines.

Then there’s the Ellison-Rinehart machinations to consider. Mineral Resources, Liontown, Alita Resources and all the shenanigans ongoing are designed to consolidate control over the entire lithium industry. For context, Liontown shares have collapsed by nearly two-thirds since Rinehart blocked its multi-billion dollar takeover by Albemarle — and the billionaire has lost an extraordinary paper sum in the process.

But neither she nor Ellison care about paper losses. They want to control the industry because they know what’s coming. Oil and gas will start to run out eventually, and lithium’s basic chemical properties cannot be replicated.

Right now, it’s uranium’s time to run. But lithium will shine again — and lithium companies simply need to survive the next 12-18 months.

The last ones standing will rocket.

This article has been prepared for information purposes only by Charles Archer. It does not constitute advice, and no party accepts any liability for either accuracy or for investing decisions made using the information provided.

Further, it is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person in any country or jurisdiction where such distribution or use would be contrary to local law or regulation.