Mortgagees are labouring under the delusion that the government will ride in on a white horse to save them from financial despair. This isn’t going to happen.

In August 2022, weeks before Liz Truss became persona non grata amongst mortgage brokers, I noted that a housing market crash was ‘inevitable.’ Since then, the Bank of England’s base rate has risen to 4.5%, CPI inflation remains stubbornly at 8.7%, and analysts who had thought an increase of the base rate to 3% impossible are now seriously contemplating a terminal rate of 6%.

According to Moneyfacts, the average two-year fixed rate mortgage has risen above 6% for the first time since 2000, while analysis by Neal Hudson shows that because of housing inflation, mortgage rates at this level is equivalent to the double-digits experienced in the 1990s.

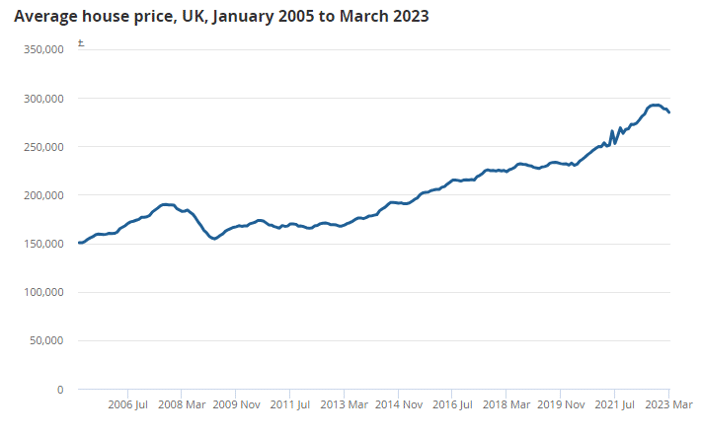

The problem is that the ONS considers that the average UK house price is still at near record highs — standing at £285,000 — £8,000 below the November 2022 peak but still £11,000 higher than a year ago. And with the ‘average’ mortgage now hundreds of pounds higher on this typical home, the new bills are simply crippling for the thousands and thousands of mortgagees exiting their fixed rate each month.

For context, UK Finance considers that more than 25% of UK ‘homeowners’ — or 2.4 million households — on a fixed rate will see it expire before the end of 2024. This rises to 4.4 million homeowners if you start from when rates began rising in December 2021. And rates are still rising.

The Resolution Foundation thinks (and I know that economic predictions are about as much use as a chocolate teapot) that annual mortgage payments will rise by £15.8 billion by 2026. Or in other words, an extra £2,900 per remortgaging household, on top of frozen tax bands, rocketing inflation, and the wider cost-of-living crisis. Worse, 60% of this timebomb has yet to hit mortgagees as millions remain on five-year fixes from before the rate hiking cycle began.

If you accept that house prices are a function of mortgage availability, then the coming crash could easily see house prices fall by 30% in nominal terms — or more. FCA data shows that the value of new mortgage commitments in Q1 2023 was 16.1% less than in the prior quarter and 40.7% less year-over -year at just £48.9 billion.

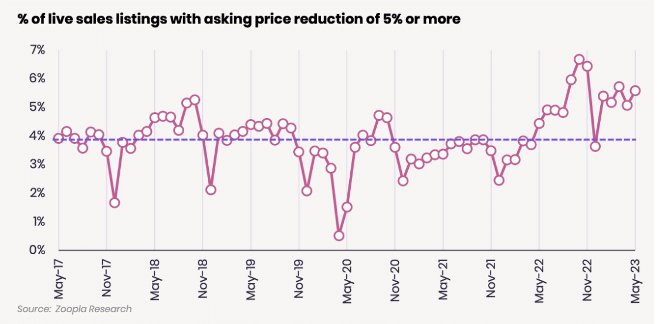

Even Rightmove — that bastion of statistical honesty — has accepted that asking prices have fallen by £82 to £372,812, and for the first time in six years. Why the disconnect between asking prices and the actual average home price? Rightmove only counts ‘new’ asking prices, and not houses where the seller has been forced to reduce their ask — leaving the data irrelevant to any serious analyst.

For perspective, reductions on asking prices on Zoopla of more than 5% are already being applied to 6-7% of homes, roughly 35% higher than the portal’s five year average.

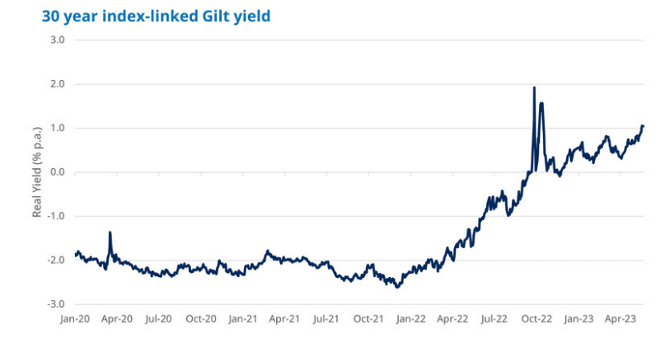

In gilt yield terms, central bank analysis from December 2019 states that average house prices would fall in real terms by 20% in the event of ‘a 1% sustained increase in index‑linked gilt yields.’ The 30-year index-linked gilt yield has snow risen from around -2.5% at the start of the year to 1% today, a 3.5% rise.

No amount of fudging will stop the housing market crash unless there is serious government intervention — which would simply push up inflation and make the problem worse.

Will there be any help?

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt has issued strong support for the much-maligned Bank of England in its campaign to reduce inflation through raising rates. While most UK inflation is either supply-side or corporate greed-induced, raising rates — like a hammer where a chisel would work — is the only tool available to get the job done.

The Treasury is clearly, and for good reason, wary of supporting homeowners directly for fear of further fuelling already sticky inflation. Arguably, the whole purpose of raising rates is to cool growth and reduce consumer discretionary income. There’s also the question of fairness — politically, the group in most danger are renters, who would not benefit from MIRAS-style mortgage support or similar.

PM Rishi Sunak has said the government can only ‘stick to the plan’ of halving inflation by the end of the year — a pledge which might have seemed easy when set, but now perhaps may not be met. He acknowledges ‘the anxiety people will have about the mortgage rates’ but has refused to commit to any other support. Michael Gove has said any possible help is ‘under review,’ but this is the same as when a four-year-old asks if they can go to Disney tomorrow and their parents say ‘maybe.’

For the opposition, Keir Starmer has refused to pledge extra specific support for mortgagees, only noting that the party would use gains from North Sea windfall taxes to reduce energy bills to as indirect assistance. Of course, this presumes that there would be any companies left to tax.

Liberal Democrats leader Ed Davey seems to want to keep the party within the comfort of electoral oblivion with a £3 billion emergency mortgage protection scheme to help mortgagees at risk of losing their homes.

He notes that ‘If we don’t give that sort of help to those people, you’d see a spiral down and it will hit the whole economy…my worry is that we’re going to see lots of other families losing their homes, and we could be in a spiral of repossessions.’ For context, mortgage repossessions rose by 50% quarter-on-quarter in Q1.

Of course, this type of support isn’t going to happen. The problem is that pandemic-era furlough payments, energy bill support, and cost-of-living payments have cossetted the general public within a ball of cotton wool — safe in the belief that the government will protect them from all manner of financial dangers like some kind of cash-rich sheepdog.

But when Liz Truss told the markets that she would guarantee energy costs for two years with no limit, she invited chaos. And mortgage guarantees or support would be a much, much larger policy — ONS data shows that from April 2016 to March 2018, total household property debt was £1.16 trillion — that’s trillion with a T — and it’s only increased since then.

The government won’t and shouldn’t come in to rescue those underwater. The housing market will fall, prices will reset, and the end of the real estate bubble will see younger people able to purchase homes without having to resort to 40 year mortgages or selling their least favourite kidney (or child). Of course, some older cash buyers will make a killing, but this reset has been a long time coming.

And to those thinking that rates will come back down to a ‘normal’ of under 1%, this is your reality check. Normal is circa 5%, and this was the case for decades before 2008. Having drunk the tonic, central banks would be mad to reverse course.

This article has been prepared for information purposes only by Charles Archer. It does not constitute advice, and no party accepts any liability for either accuracy or for investing decisions made using the information provided.

Further, it is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person in any country or jurisdiction where such distribution or use would be contrary to local law or regulation.