Teaching financial concepts young is as vital as learning to ride a bike. At least, that’s my position.

There are certain life skills that you need to impart to your children before you let them loose on the world at around the age of 18.

For most, this includes how to drive, swim, ride a bike, make popular cocktails, tie a tie, change a tyre, cut a cigar, put up a shelf, build flat-pack furniture, acquire ABRSM piano grade 2, and also imbue a reasonable level of confidence…these aren’t things that you are unlikely to be taught in school; they’re parental responsibilities.

In other words, you should be teaching your children how not to be a useless person. Generally, most parents cover the basics but one area where many fail is personal finance — and in particular investing. Now, I’m at an advantage because stock market analysis is my full time work and I usually work from home — so my three sons pick up a lot of knowledge via osmosis.

But just like the above life skills, this is not enough. You need to teach children how to invest properly, because there’s a reasonable chance that at some point they’ll open a Twitter account, download TikTok and take useless advice from FinTok, or even join a Telegram Group.

They might even wander into the FTSE AIM market — and let’s be honest — a certain Obi-Wan Kenobi quote fits this particular bazaar at times.

If this isn’t enough motivation, here’s some motivation for you: If your children don’t have a nest egg they can’t move out. IFS data shows that 45% of first time buyers between 20 and 29 get cash from relatives to buy (averaging £25,000) and I would hazard a guess that the remainder who manage to get on the ladder are living at home for a decade to save up.

No family support or nowhere to stay rent free? Your sproglet is renting forever unless they live somewhere very cheap (far away from you) or get a very above average job. And this all compounds of course, because if your children buy a house early, they’ll pay the mortgage off early while also seeing longer real estate capital growth. They’ll almost certainly also be much happier.

And on a personal finance level, if you can help get them on the ladder, they will be far less likely to be a financial drain on you too.

Over the longer term, investing confidence is just another life skill — and an educated 18-year-old will have a much better time of it than a 55-year-old who starts Googling ‘what is a pension?’ only a decade before retirement.

Child Accounts

There are three accounts to consider when investing on behalf of your children:

- Junior ISA (JISA) — annual account deposit limit of £9,000, paid in from net (after tax) income. Capital gains and dividends are not taxed, though your child gains complete control of the account at 18.

- Your own ISA — annual account deposit limit of £20,000, paid in from net (after tax income). Again, capital gains and dividends are not taxed, but the key advantage is that you control when to give the cash to your child. Of course, there are IHT implications and also the risk you spend it yourself in a pinch.

- Junior SIPP — few know this, but you can put £2,880 into your child’s pension a year and the government will top it up with 20% tax relief to £3,600. Control goes to your child at 18 but withdrawals are either punitive or impossible until retirement (age 57 from 2028). This is more tax efficient — again gains and dividends are not taxed — but while it may feel far less flexible, allows your child to ignore pension saving in favour of building a deposit up faster.

Once you’ve chosen an account, the next question is: what investment is best? I can’t give advice, though the S&P 500 has delivered an average 11% annual return since 1957. You can get lower returns on the FTSE 100 or through a world tracking index — and higher if you pick stocks in exchange for elevated risk.

But for context, let’s say you have two children. You automatically deposit £50 per month each into their JISAs from birth and manage to generate an average annual return of 10%. After 18 years, they should have circa £30,000 each including £19,000 in investing returns. Keep going until they’re 21 and that’s over £42,000 each — that’s the magic of compounding. Stop investing on their behalf at 25 and it’s over £66,000. Each.

And yes, you need to consider inflation — and also the reality that an additional £100 per month is beyond many people right now. But typical readers here should understand: if you don’t prepare your children for financial adulthood, the person whose finances will be hit hardest is yours.

As a caveat, I am not a financial adviser. But the days when you could send your 18-year-old out into the world and let them make it on their own are gone; the decisions you make now can give them a fighting chance.

Teaching investing to children

Children tend to be resistant to anything that looks a bit boring, so how do you get them engaged?

I’d start by asking them (from the age of about 8 — or whenever they can properly grasp chess concepts) to name ten companies they come into contact with — you’ll hear the big names — Tesco, Amazon, Mars, Google etc. Remember, they have no concept of relative market size.

Then log onto your preferred account and literally buy £10 of each company with them sitting beside you, though make sure to use a ‘free’ trading account for this. Let them press the buy button and tell them that they can keep any profit made, and they can check back in a week. Whenever the ‘portfolio’ is slightly up, show them how to sell — and then give them the profit in cash and take them to a shop to buy chocolate.

Next week, do the same thing but explain that (as a general rule) the longer they stay invested, the more money they make. If your children are anything like mine, they will then want to check the dashboard every day and you can start to work in basic concepts like revenue and profit. Keep it age appropriate though, as adjusted EBITDA can sound like accounting fraud if not explained and understood properly.

Tell them that they can spend the profit generated when the portfolio goes up — but that if they prefer, they can keep invested to generate higher returns. Let them make the decision each week; eventually they will choose to try to make more money.

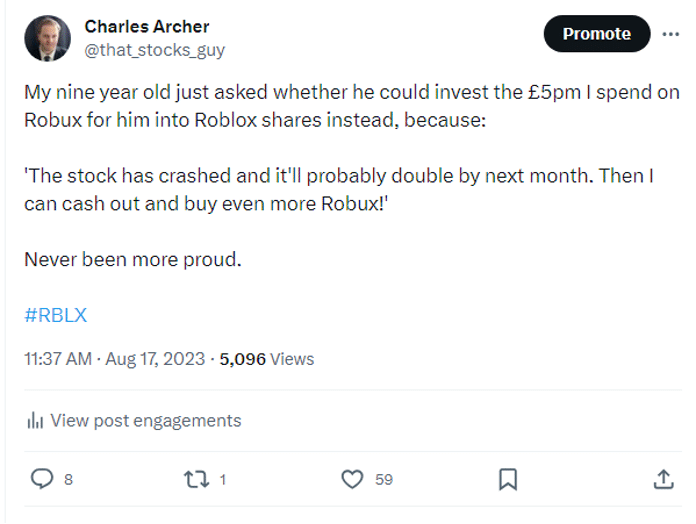

Once they attach chocolate returns to portfolio performance, then you’re away. In fact, my nine (now ten year old) asked me to buy the dip in Roblox in mid-August, instead of the game’s in-world currency, after the crash. He had to wait out the drop from his initial position of circa $28 to $25 during late September, but the recovery has seen the stock rise to $40 since.

Not quite doubling by next month, but his sound reasoning was that children aren’t going to stop playing the game and everybody he knows keeps buying Robux. I’m not as sold on this particular inelasticity of demand — but you can’t fault a 40% return in less than four months.

A word of caution: don’t introduce children to the AIM market until they get a bit older, perhaps 13. Perhaps also steer clear of CFDs.

But introduce them to investing early? It doesn’t have to be at the age of 8, but for responsible parents, it’s non-optional home education.

This article has been prepared for information purposes only by Charles Archer. It does not constitute advice, and no party accepts any liability for either accuracy or for investing decisions made using the information provided.

Further, it is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person in any country or jurisdiction where such distribution or use would be contrary to local law or regulation.

You might also be interested in: Start a business or start investing? From a tax perspective, it’s an easy choice