As Nord Stream One closes indefinitely, soaring gas prices mean the opening up of both painful choices and rare investing opportunities.

Gas is now the UK’s foremost political and economic problem.

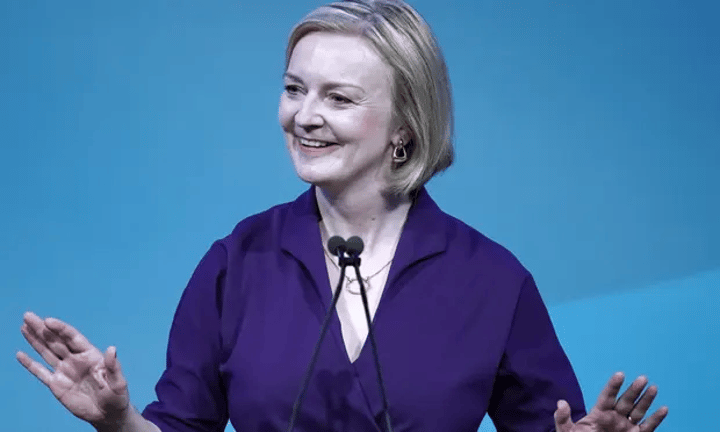

The country has a new Prime Minister whose instincts are to avoid ‘handouts,’ but will nevertheless be forced to give them out.

Meanwhile, the G7 countries have agreed to put a price cap on Russian oil. Signatories are prevented from purchasing Russian oil transported by sea for more than the cap level.

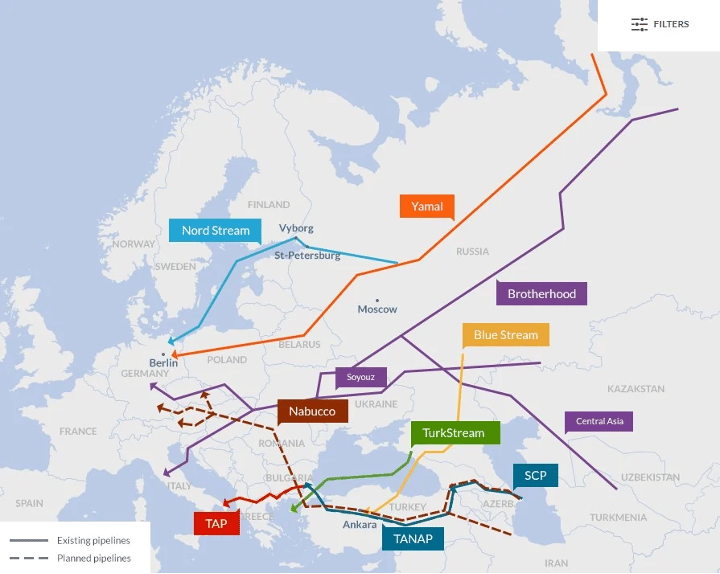

In response, Russian gas from Nord Stream 1 is being suspended indefinitely. And Russia has warned that gas supplies will not resume in full until the ‘collective west’ lifts all sanctions.

Where next for gas prices?

The Dutch month-ahead wholesale gas price, a key European benchmark, is up over 30% today, wiping out prior falls after Germany announced its storage was filling up faster than expected last week.

The UK’s annual consumer price cap for the average household is already at £3,549, and is expected to rise by thousands in January, and again in April. The exact numbers are becoming meaningless as October’s rise is already unaffordable for millions.

UK businesses are not covered by the price cap, and gas prices are up by a factor of 11 compared to pre-pandemic levels. The British Chambers of Commerce has warned thousands of firms will ‘close their doors this winter’ without support.

In other European nations, action is already being taken. Germany plans for a windfall tax-funded £56.2 billion package that will support both the least well-off, and energy-intensive sectors. Sweden and Finland have proposed similar measures.

But here’s the rub. The covid-19 pandemic had already seen many smaller oil and gas producers shut down permanently. With supply constricted, post-pandemic demand had already increased gas prices to an unreasonable level before the Ukraine war.

And Russia supplied 40% of the EU’s gas in 2021.

Not only is this seeing record, unaffordable prices, but this supply cannot be replaced in time for winter.

The truth that politicians refuse to admit is that high prices are merely a symptom of the disease. Nearly half of Europe’s gas supply has been wiped out, and there now isn’t enough to go around.

This potentially leaves just three possible outcomes this winter: energy rationing, blackouts, or capitulation to Russia.

Investing opportunities

How will PM Truss respond to the crisis? Sadly for the new premier, she doesn’t have many choices.

A consumer price freeze at the current level seems unavoidable. How this will be paid for is subject to debate; forcing energy suppliers to take on debt, nationalising producers, imposing windfall taxes, or increasing government debt are all possibilities.

Businesses could see another ‘bounce back’ style scheme that ostensibly keeps them alive over winter, but just kicks the can of unaffordable debt further down the road.

Of course, both actions involve more money printing; numbers exceeding £100 billion are being thrown around with casual abandon. And Truss has already promised significant tax cuts to boost the economy.

The result could be even higher inflation, further weakening Sterling, putting pressure on the Bank of England to increase the base rate far higher than the 4.1% expected by city economists by mid-2023.

The Bank has already predicted a severe recession that will last for five quarters starting in Q4. For context, this is as long as the 2008 financial crisis.

Investing opportunities will be few and far between, especially if demand destruction sets in.

However, it’s possible to speculate on potential energy trends.

First is the effect on energy producers operating on the North Sea: BP, Shell, and Harbour Energy.

The current windfall tax allows for a 91% reduction based on further investment in North Sea-based exploration. This could be amended to include a hedging, or options clause, whereby the UK retains the right to purchase this oil and gas at a below-market price.

Second is the possibility that green energy will be uncoupled from the coal-powered generation peg. Ofgem has already suggested splitting the wholesale market to delink renewably-sourced energy production from fossil fuel production.

In 2020, renewables accounted for 43.1% of the UK’s electricity generation, and 42.8% between October and December 2021. This proportion has increased tenfold since 2004, and the country now also boasts the world’s largest offshore wind farm, Hornsea 2.

With energy security now political priority number one, green tax incentives could be in the offing. The implications — both positive and negative — for renewable champions such as SSE are remarkable.

Third is the potential for accelerated changes to the UK energy mix.

Onshore fracking could become far more widespread; when gas shortages start to bite, the political calculation could change in favour of allowing fracking as default.

Likewise, public opinion on nuclear power could change in the cold of winter. Uranium, and its miners, could be about to see huge demand as opposition wanes. Further, demand for solar panels is already exploding, with Egg seeing an 830% increase in enquiries compared to this time last year. Business Secretary Kwasi Kwarteng, tipped to be Chancellor, aims to triple solar production by 2030.

Of course, speculating is not a risk-free endeavour.

This article has been prepared for information purposes only by Charles Archer. It does not constitute advice, and no party accepts any liability for either accuracy or for investing decisions made using the information provided.

Further, it is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person in any country or jurisdiction where such distribution or use would be contrary to local law or regulation.