Meddling with pensions is always a recipe for disaster. Stop tinkering and get the tax burden on earnings down instead.

As a higher-rate taxpayer with three delightful but dependent children, there is nothing quite so brutally tax efficient as contributing excess income to a private pension (SIPP).

I’ve covered the oddities of the UK’s personal tax system before, but in brief the £10,000 earnt between £50,000 and £60,000 is subject to corporation tax, dividend tax, undergraduate and postgraduate student loans, in addition to the high income child benefit charge.

Overall, this would leave me with a marginal rate of circa 80%. Further, income earnt between £100,000 and £125,000 can actually be charged at a marginal rate of higher than 100% once all deductions are taken into account.

Putting any earnings above £50,000 into a pension not only avoids these deductions, but also means that when I come to withdraw, all my student loans will have been wiped, while I will hopefully also no longer be claiming child benefit.

You might think that I would therefore be delighted with the unofficial budget update that pensions savings is about to become far more lucrative. While I do stand to benefit, I also have some concerns.

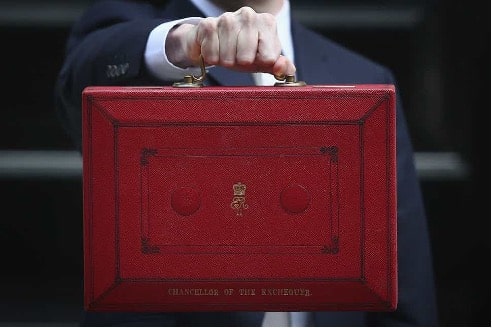

Budget 2023: pensions changes

While the Chancellor has clearly asked the media to conduct an unofficial poll of support, it seems very likely that two key changes will be happening in the next tax year.

First, the total amount that can be accumulated in a private pension before paying excessively punitive tax rates — the lifetime allowance — is set to increase from the current £1,073,100 to £1.8 million. This new policy is designed to stop people from retiring early — in particular skilled staff in shortage sectors such as medicine and business consultancy.

Second, the annual amount that can be saved into your pension is being increased from £40,000pa to £60,000pa. This is a welcome step for many professionals who cannot make the maximum contribution in their younger years but are then restricted by the annual limit rather than the lifetime allowance as they age. At present, you can only make use of the past three tax years’ worth of unused contributions.

To be fair to the Chancellor, there are good economic and social reasons for the changes. UK productivity is in decline, the country faces a recession, and the over-50s — fairly or not — are government targets for getting back into work. Meanwhile, the NHS is understaffed and needs more doctors to remain in service, and London is certainly in need of the expertise of experienced consultants to weather the current storm.

What Hunt misunderstands

Let’s consider the reality of saving for retirement. The idea is to provide a certain level of personal comfort while also reducing reliance on the state for when you are no longer working. However, the UK population is now enduring the highest tax burden since the Suez Canal Crisis, and this is only getting worse.

Corporation tax is rising from 19% to 25% for most companies, the dividend tax allowance is a pitiful £2,000, and dividend tax rates have risen by 1.25 percentage points this year alone. This is creating an insane situation where Hunt may achieve the exact opposite of what he hopes.

He may encourage current 50+ year-olds to defer retirement, but those of us in our thirties are now hugely incentivized by a lopsided tax system to feather an even larger nest, making retirement easier in the future and compounding the current problem. Or in other words, he’s robbing Peter to pay Paul.

But more than this, Hunt is creating a situation where ‘pensions’ saving is now about reducing one’s personal tax burden rather than creating a provision for retirement. Of course, tax incentives are an important component of encouraging people to think about retirement, but the government is essentially robbing the economy of liquidity by over-encouraging pensions savings.

But while this is an important point, the principle problem is that it is becoming completely impossible to plan for retirement. Up until the days of Gordon Brown, pensions were a largely settled matter, and people knew that the rules would stay static whether they were five, 10, 20, or even 40 years from retirement.

But that certainty no longer exists. Forgetting the insanity of IR35 rules, a reform of which would be a much easier way of getting professionals back into the workplace, I have no idea what conditions my pension will be under when I retire.

Consider this: the lifetime allowance was already set a £1.8 million in the 2011/12 tax year, reduced to as low as £1 million by the 2016/17 tax year, and is now set to rise again. In the 2013/14 tax year, the amount that could be contributed was £50,000, this was lowered to £40,000 the year after, and is now set to rise to £60,000.

That’s to say nothing of the need to reform the money purchase annual allowance — which again has been tampered with by meddlesome politicians — to ensure that people who have already withdrawn pensions cash can make use of the new ceiling. There’s also questions over fairness to those who have already made financial decisions based on the current rules.

Further, there are already rumblings that pension savers who can currently withdraw 25% of their pot tax-free upon reaching 55 will see this benefit limited or cancelled. And this age is set to reach 57 by 2028 and will likely be later by the time I get there.

In addition, as a person in my late thirties, I am absolutely certain that the current state pension is unsustainable, and will either be scrapped entirely, see eligibility raised to a high age-related ceiling, or means-tested long before I reach retirement age.

Taxpayers need certainty when it comes to pensions. Stop meddling.

This article has been prepared for information purposes only by Charles Archer. It does not constitute advice, and no party accepts any liability for either accuracy or for investing decisions made using the information provided.

Further, it is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person in any country or jurisdiction where such distribution or use would be contrary to local law or regulation.