The UK housing market has long been an unassailable economic force. Until now, that is.

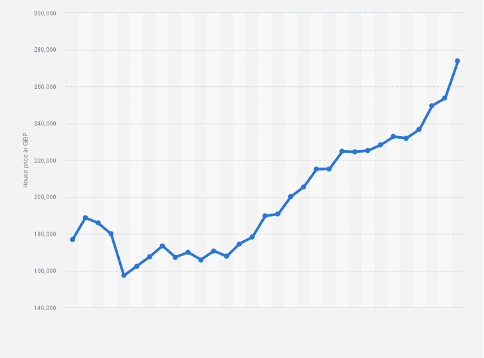

According to the ONS, the average UK house price now stands at a record £286,000, an increase of 7.8% over the past year. For context, it was just £157,200 in 2009.

While a further increase is possible, a substantial fall over the next 24 months appears more likely than not.

House prices: a history

Getting to this record high has not been an accident. Homeownership rose from 55% in 1979 to 71% by 2003, fuelled by right-to-buy legislation seeing council housing units fall from 6.5 million in 1980 to just 2 million today.

As the housing market became increasingly financialised, the decade leading up to the 2008 credit crunch saw prices triple as mortgage lending increased by 400%.

After 2008, interest rates fell to below 1%, and stayed there until December 2021. With prices rising fast, the government introduced multiple ISA products for first-time buyers, including the current Lifetime ISA.

Covid-19 pandemic-induced panic then saw it act to prop up prices, declaring a stamp duty holiday between July 2020 and September 2021.

At the same time, a combination of forced savings, furlough, and increased government spending saw household savings as a proportion of resources increase to 23.9% in Q2 2020. This created an additional £140 billion of savings, much of which poured into the housing market.

Simultaneously, the social effects of the pandemic saw a mass exodus of buyers from cities to country in a ‘race for space,’ exacerbated by the remote work phenomenon.

Then there’s the immigration effect to consider. Immigration has exceeded emigration by more than 100,000 every year since 1998. In mid-2020, the non-UK-born population had risen to 9.2 million out of an estimated 67.1 million.

For context, only 216,000 new homes were built in FY20/21, partly due to the small number of housebuilders with the resources to build.

The result? Prices rocketing on unsustainable policy.

Where next for house prices?

Consider the post-Brexit, post-pandemic UK. Already, rising prices have seen homeownership decline to 63% by 2017.

Immigration is falling due to Brexit, with 43,000 EU citizens receiving visas in 2021, down from 230,000 to 430,000 arriving in the six years to March 2020. Demand is falling.

CPI inflation is at 10.1%, and Citi predicts it will strike 18.6% by January. The inflationary catalyst is energy costs, with the UK’s average household’s annual energy bill rising to £3,549 a year in October.

In its latest forecast, Auxilione has predicted this will rise to £7,700 by April. And this augury keeps rising. Moreover, there is no price cap for businesses. Many smaller companies will collapse this winter as costs rise while spending decreases unless there is hundreds of billions of pounds of government intervention.

There could soon be an unemployment crisis just as every essential bill is rising. Further, with the base rate already at 1.75%, the markets are pricing in an increase to 4.1% by mid-2023, adding hundreds to the average mortgage.

Simultaneously, the help-to-buy scheme, which allows first-time buyers to purchase homes with a 5% deposit, is ending in March 2023.

Meanwhile, constant legal changes to buy-to-let are making it a far less appealing investment choice. Landlords are selling up in droves as they can no longer deduct mortgage interest payments from rental income before paying tax. Instead, the sum has only qualified for 20% relief since 2020.

Further, stricter EPC regulations and a tenant-favouring Renters Reform Bill are coming, just as renters’ ability to pay their rent becomes ever more precarious.

Meanwhile, current mortgagees are highly incentivised to stay put for the duration of their fixed-term deal, as moving will entail hundreds in extra interest payments. But when their fixed deals end, they may find new payments unaffordable.

The recently scrapped mortgage stress test includes the capacity to cope with a 3% interest rate hike, but there are no guarantees rates won’t go higher. Further, the test is considered in isolation, without considering the additional stress of rising essential bills.

Institutional investment believes a crash is possible. The UK’s largest housebuilders, Persimmon, Taylor Wimpey, and Barratt Developments, have all seen their share prices nearly halve year-to-date. And Lloyds Banking group, by far the UK’s largest mortgage lender, notes that the house price to income ratio now stands at 7:1, meaning that property affordability is at its most stretched ever.

The key limiting factor for UK house prices is the availability of mortgage credit, as 90% of buyers over the past five years have used a mortgage to buy.

But rising interest rates mean that monthly mortgage payments are rising while skyrocketing inflation is putting pressure on discretionary income. Simultaneously, a severe recession is coming, with the Bank of England expecting it to continue for five quarters starting Q4 2022.

Further, the house you buy is the collateral for your mortgage loan. But if the house price drops below the loan value, the subsequent negative equity can mean disaster on a mass scale. This means banks will limit the amount they are willing to lend, with more down valuations likely.

With international energy markets outside of Westminster’s control, intervention on the scale of the pandemic seems unaffordable.

A crash is coming.

This article has been prepared for information purposes only by Charles Archer. It does not constitute advice, and no party accepts any liability for either accuracy or for investing decisions made using the information provided.

Further, it is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person in any country or jurisdiction where such distribution or use would be contrary to local law or regulation.