Chinese expansion into emerging markets and a western laissez-faire approach to boom-and-bust commodity cycles could see shortages materialize next year.

Copper is one of the most important industrial metals on earth. Its ductile, exceptionally good at conducting electricity, and is used in devices including electric vehicles, smart phones, solar panels, and wind turbines all of which will power the decarbonised future. And demand is growing; according to the Copper Alliance, EVs use twice as much copper as ICE cars.

Globally, 21 million metric tons of copper are mined every year, but it’s not going to be enough. Over the next 20 years, the International Energy Agency expects it to become a dominant mineral alongside graphite and nickel, with demand set to treble by 2040 as net-zero goals accelerate.

Commodities trading firm Trafigura has already warned that the global supply of copper remains dangerously low, despite wider fears that a global recession will push demand down next year.

Cohead of metals and minerals trading Kostas Bintas has warned current inventories can only cover 4.9 days of global consumption, and this is likely to drop down to 2.9 days by the end of 2022. This is partially a consequence of the just-in-time globalised model, which has been unclothed by a toxic cocktail of the pandemic, Ukraine war, and subsequent supply chain crunch.

For context, copper inventories had historically been sufficient to last several weeks. And while Bintas notes the ongoing collapse of China’s property market amid lockdown concerns, he argues that the growth of renewable energy demand more than compensates. It’s not hard to understand why, as the EU, UK and US have all set aspirational net-zero targets for the next few decades.

Accordingly, the oldest economic rule — constricted supply and increased demand pushes up prices — could be in play, with copper no exception.

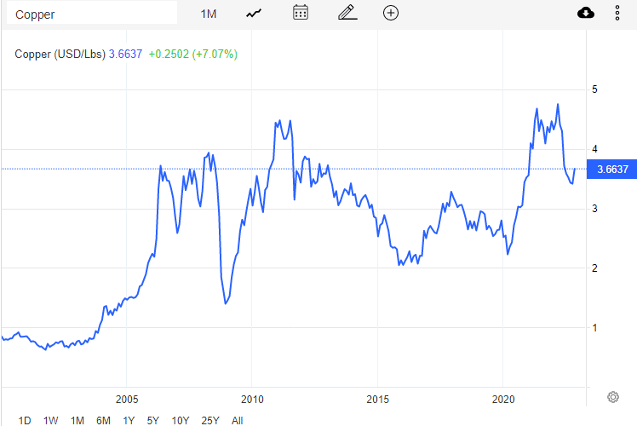

The metal is currently trading for $3.66/lbs, having dropped by circa 30% from its high earlier this year. But this could just be the calm before the storm, as global recession fears are trumped by the lack of overall supply.

Freeport-McMoran has also cited risks of shortages, with the relatively low current price not underpinned by the tightness of the market. It’s also worth noting that the two largest copper mining countries — Chile and Peru — are seeing output drop as older mines degrade and new sources become harder to find.

Meanwhile, emerging markets such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Zambia are seeing output accelerate. Zambian Finance Minister Situmbeko Musokotwane recently enthused that ‘copper is the new oil.’

CRU Group analyst Adam Khan notes that Zambia could add nearly 1 million tons of copper production per year over the next decade, while Congo’s output has already tripled in the past ten years, and according to Darton Commodities is set to increase by a further 79% by 2025.

Further, Fastmarkets metals analyst Boris Mikanikrezai warns that China’s dominance in emerging markets means that the west could be in ‘more trouble’ than first appears. The Asian superpower’s painstakingly slow acquisition of copper assets over the long-term could be putting it at an advantage of the capitalistic boom and bust periods experienced by western economies.

In his own words, ‘if you look at how the Chinese deal with African mining, you can see the objective is to secure metals over the long-term. While, in the West there is more of a short-term view based on cycles.’

Conversely, BHP CEO Mike Henry argues that ‘the world’s not going to run out of copper. We can be very confident about that…there’s more than enough units in the ground to meet the world’s need for those commodities.’

However, he conceded that if supply problems continue, copper prices could rise to make it worth developing currently uneconomically feasible mines, with the risk being that there could be a ‘mismatch between the timing of increase in demand and when supply meets that demand.’

Where next for copper prices?

As copper mines take circa ten years to come online, price stability is a necessity to ensure that the costs of development will be paid back. Rio Tinto CEO Jakob Stausholm acknowledges that ‘significant investment in copper does require a good price, or at least a good perceived longer-term copper price.’ Already, Newmont has rowed back on plans to open a $2 billion gold and copper mine in Peru.

The problem is that while copper prices could soar in the long term, they are likely to drop in the near term.

Inflation has driven up production costs by as much as 30%, and the cyclical nature of commodities mean that investors wary of falling demand aren’t prepared to invest in new mines that could in theory be unprofitable while in development. Instead, miners are taking the certainty of dividends and share buybacks that are always popular with investors.

Indeed, Jefferies analysts cite ‘the incentive to use cash flows for capital returns rather than for investment in new mines (as) a key factor leading to a shortage of the raw materials.’

With mine supply growth set to peak in 2024, the world could see a deficit of 10 million tons in 2035 according to S&P Global. Goldman Sachs research shows that miners need to collectively invest $150 billion in the next decade to plug this gap. And Bloomberg Intelligence thinks this unrealistic, arguing that the gap will hit 14 million tons by 2040.

In 2021, the shortage gap — the difference between copper mined and demand — came to just 2% of production, enough to push up copper prices by 25%.

2035’s gap could be at least ten times as much.

This article has been prepared for information purposes only by Charles Archer. It does not constitute advice, and no party accepts any liability for either accuracy or for investing decisions made using the information provided.

Further, it is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person in any country or jurisdiction where such distribution or use would be contrary to local law or regulation.